What are oxalates and how do they affect your health?

Every so often I am introduced to an old concept in a new and different way that helps me find a missing puzzle piece to a patient’s condition. Kind of an “ah ha” moment in my own mind that leads me to conclude that maybe this is a layer in a patient’s chronic condition that was previously unclear.

Oxalates are one good example of this. Having high levels of oxalates could potentially affect patients with chronic aliments and be so misunderstood that they’re not on your practitioner’s radar. Oxalates are produced by plants and are naturally occurring to protect plants – the leaves and roots make the most oxalates. When doctors think of oxalates, we typically only think of them in the context of an issue in kidney stone formation. However, they are involved in many more processes.

Elevated oxalates can cause a variety of issues from kidney stones to joint pain, from structural challenges to styes, from chronic bladder pain to chronic pain. In this blog, I hope to share some information that could help you discover whether elevated oxalates are an issue for you.

There are two main ways we are affected by oxalates:

Primary Oxaluria. This is genetically driven by 2 genes: AGXT and GRHPR. These genes are responsible for less than 1% of all kidney stone presentations.

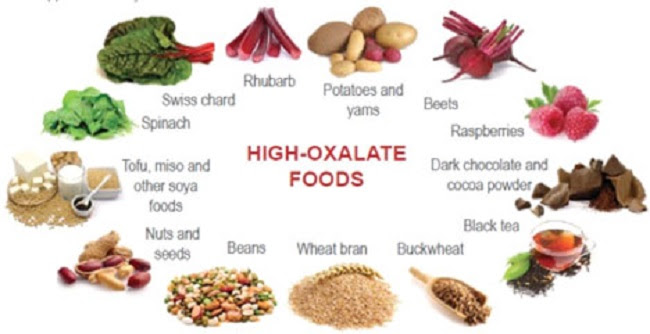

Secondary Oxaluria. Most causes of elevated oxalate levels are due to secondary causes, such as dietary exposure from foods like spinach, rhubarb, almonds, and beets. Diet can be the biggest cause of hyperoxaluria (elevated oxalates in the urine).

How do we get exposed to oxalic acid?

Diet and Lack of Nutrients

Oxalic acid from plants in our diet is bound to minerals, and this complex forms insoluble crystalline precipitates. These are micron-sized complexes that shred surrounding tissues like tiny knives. When in excessive levels, oxalates are a detriment to health. Patients who suffer from chronic pain might in fact be suffering from the shredding of tissue from these precipitates that build up in connective tissue, joints, or muscles. Dietary insufficiencies, such as low amounts of B6, B1, or sulfate can contribute to hyperoxaluria. The dietary component is not simply one of excess oxalate consumption. It is a problem with inadequate nutrient consumption in the face of excessive non-nutrient foods (i.e., processed foods) – e.g. it is a problem with the modern western diet in its entirety.

Fat Malabsorption

If you do not happen to digest fat well, oxalates could build up in your system and become a problem. Undigested fats bind to minerals in the GI tract, which increases absorption of dietary oxalates. This often happens with low bile flow, lack of a gallbladder, or poor digestion of fats.

Mold Exposure

Being exposed to aspergillus niger (a toxic mold from water damaged buildings) increases oxalate production as a fermentation by-product. Patients who experience mycotoxin illness or who have been exposed to a water damaged building will likely have elevated levels of aspergillus niger, and this creates more oxalates.

Gut Permeability

Gut permeability allows absorption of more oxalates into the bowel that normally would be excreted out through the bowel.

What do oxalates do?

(This is an overview. There are many other issues caused by high oxalates.)

- Oxalates make crystals that can tear tissue or joints leading to pain.

- Oxalates contribute to the formation of kidney stones. 60-80% of stones are calcium oxalate stones, yet only 0.5% of people with hyperoxlauria will develop kidney stones.

- Oxalates bind to sulfate receptors in body and do not show up on traditional imaging, such as an X-ray or ultrasound until they are very large. Where they bind determines where the pain is located – structural instability or joint pain muscular pain, fascial pain, ocular issues, intra-ocular eye pressure, stye formation, COPD, pulmonary fibrosis, fibromyalgia, vulvodynia (vulvar pain syndromes), or interstitial cystitis.

- Oxalic acid is a potent chelator when bound to minerals and heavy metals. It binds easily to calcium and has strong affinity for magnesium (could this contribute to the frequent cause for magnesium deficiency?). It also binds to iron and ferritin and could contribute to the cause of anemia.

- Connective tissue relies on sulfate levels being adequate for structural stability. If oxalates are high, they will displace or replace the sulfate, causing a weakened connective tissue. Issues that can result from this are Elrhlos Danos syndrome, hypermobility, and not being able to hold a chiropractic adjustment leading to constantly being “out” of alignment.

- Oxalates bind to sulfate receptors, causing loss of the sulfate molecule. This causes us to lose sulfation of hormones, causing hormonal dysregulation, PMS, shredding of tissues, which can contribute to ovarian cysts and uterine fibroids.

- Oxalates and MCAS (mast cell activation syndrome) have a relationship – oxalates are a direct trigger to create inflammation/activation of mast cells. If you have been diagnosed with MCAS, consider looking into your oxalate levels.

Testing

The tests currently available to evaluate oxalate levels are urine tests that are essentially measuring “excretion”. That means if your levels are high, review dietary intake for the previous few days to ensure that the results are not reflecting high oxalate dietary intake. Consider repeating to verify. Slightly elevated levels may not be a concern, but levels that are 5-10x the normal range would reflect more than dietary absorption of oxalates. Often patients with the biggest issues with oxalates (not related to frequent exposure before the test) are not excreting them. This is why they are a problem: they are building up.

The Organic Acids Urine Test from Great Plains Laboratory has 3 markers that can help your practitioner evaluate your oxalate levels.

Blood levels of LDH, if they are under 160, can indicate the need to look at excretion tests.

Treatment

- Oxalate Reducing Diet – It is important to go slow but steady to avoid “dumping” oxalates. Reduce gradually, about 5-10% weekly. Goal for chronic stone formers is 50mg/day total (it’s rare to need to be this strict). Biggest foods to avoid: spinach, chard, rhubarb, and beets.

- Vitamin B6 (Pyridoxine) – B6 is the biggest intervention for primary or genetic disposition to kidney stone formation. B6 doesn’t have an upper limit so take a high dose for kidney stone formers. I recommend 100 mg a day to start.

- Vitamin B1 (Thiamine) – By a complicated biochemical process, a deficiency of B1 leads to higher than normal levels of oxalates. Taking 50 mg per day will help reverse this.

- Epsom salt baths to replenish sulfate and help balance oxalate levels. Oxalic acid travels through body on sulfate transport and binds to transported receptor sites. You can push oxalates off sulfate receptors by introducing sulfates. If you are very sensitive, try just soaking your feet in an epsom salt bath for a few treatments before diving in all the way.

- Address any mycotoxin exposure, measure urinary mycotoxins, and assess aspergillus niger concentrations.

- Magnesium Citrate prevents oxalate formation because it has a strong affinity or binding capacity for oxalates, preventing them from being available in tissues.

- Take minerals at the end of the meal to capture and bind to oxalates.

- Stay hydrated. Drink at least 50% of your body weight in ounces and more if you workout. (e.g. a 150lb person should drink at least 75oz water per day)

Avoid

- High dose vitamin C

- Foods high in oxalates, especially if you are unsure if this is problem for you. But it’s best to confirm via testing because these foods are otherwise good for you!

- Fermented foods

- Celery juice